Silent Hill f launched two weeks ago, and is for all intents and purposes the first new entry in the series since 2012’s Silent Hill: Downpour. Without getting too deeply into the nitty gritty which I’m sure you’re sick of hearing by now, to say that Konami’s psychological horror series has been through the ringer since then would be putting it lightly.

Many would argue this has been the case since the disbandment of Team Silent following the release of Silent Hill 4: The Room in 2004, but the cancellation of Kojima Productions’s Silent Hills in and subsequent banishment to pachinko hell is a fate worse than death for one of the most influential horror franchises in the entire medium.

Due to its infancy as a medium and the all-consuming dread of capital, “death of a franchise” is not something that exists much in the AAA video game industry. Once a series of games enters a certain level of brand recognition or identifiability, it’s usually either kept alive through creative zombification because it simply won’t stop making its executives money. Or through thoughtful iterative reinvention that is usually the result of bold risk taking (or both eventually if you’re Silent Hill’s main survival horror contemporary Resident Evil). With few exceptions, the majority of enduring IP in the video game industry exist because of the safety net that banking on them provides executives and publishers.

The (Concerning) Return of Silent Hill

This was why I had my expectations set incredibly low during Konami’s announcement of a “Silent Hill Transmission” showcase in October 2022. The idea of Konami reviving Silent Hill after a decade of creative meddling during the post-Team Silent days and the huge public fallout and mistreatment of Hideo Kojima and his studio during the production of Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain and Silent Hills, seemed like nothing more than a major publisher that once seemed completely uninterested in its artistic legacy or it’s audience cashing in on the now successfully revived survival horror genre.

These fears were seemingly confirmed with the reveals of a Silent Hill 2 remake from (at the time) controversial horror game studio Bloober Team, jumping on the train of classic horror game remakes popularized by Resident Evil and mimicked by other legacy horror franchises like Alone in the Dark and Dead Space at this point in time.

This showcase also revealed the disastrous Silent Hill: Ascension, a trainwreck so catastrophic I won’t even begin to humor it here because it would just take too many words to try and explain the mess this was always destined to create. Needless to say, perhaps with the exception of the still mysterious Silent Hill: Townfall (which we still know very little about) it seemed like Konami was up to its old tricks.

Silent Hill f

That is, until the final reveal of the showcase. A 1960s rural Japan-set psychological horror game named Silent Hill f from a relatively unknown studio named NeoBards, to be written by Ryukishi07, the author behind the cult horror visual novel series’ Higurashi: When they Cry and Umeniko: When they Cry.

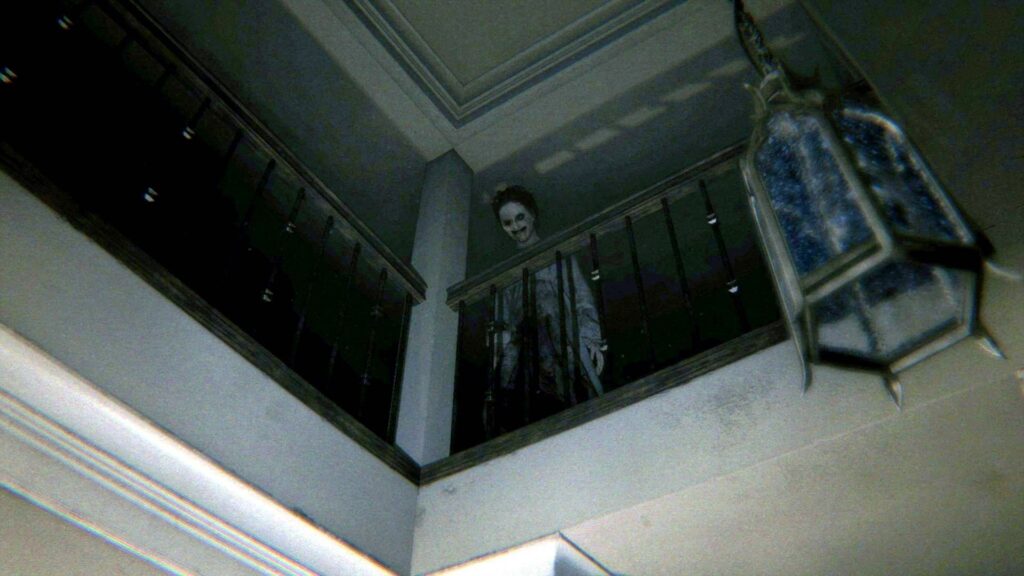

It was obvious from the haunting rendition of the original Silent Hill’s main theme and the gruesome, trypophobia-inducing imagery that there was something special to this fully original new entry that was being pushed forward by some fresh creative talent. While series composer Akira Yamaoka was confirmed to return, he’s joined by Kensuke Inage to provide authentic traditional Japanese instrumentation for the Otherworld.

The art this time would be done by “kera”, an incredible horror artist who had previously worked on the Spirit Hunter series, and, of course, the team at NeoBards would be leading the project as their first major AAA single-player title. While in the past this has been cause for concern, with Silent Hill: Homecoming and Downpour also being debut titles, the blending of creatives with a fresh development team lent a lot of spirit to the reveal of Silent Hill f and gave me a glimpse of optimism amidst an otherwise rather concerning slate for a series already decidedly hung out to dry.

Before anyone gets annoyed at my recounting of my initial response to Bloober Team’s Silent Hill 2 remake, the final project was, to me, the first sign that Konami and the teams it had optioned to revive Silent Hill were on the right track. While I liked elements of Silent Hill: The Short Message, namely its monster designs by Masahiro Ito and music by Akira Yamaoka, it was unfortunately a very messy game that blundered a lot of its central themes and featured some very questionable design choices.

It also represented a very bizarre move from Konami trying to rekindle the fires of P.T. despite their erasure of the project, but that’s neither here nor there. Silent Hill 2 remake on the other hand proved that not only was Bloober Team capable of retaining and expanding on the elements that made Team Silent’s work so beloved, but that Konami seemingly wasn’t interested in watering them down, as the work retained its maturity and nuance as a story. This worked out very well for a remake, given the rather awful writing of The Short Message, but it was certainly a concern of mine going forward for any future Silent Hill entries, especially ones written by a creator as beloved as Ryukishi07.

“Not Silent Hill Enough”

Thankfully, when Silent Hill f released just over two weeks ago, the major concerns with the game stemming from both the community and the otherwise wider survival horror audience were not with much of the narrative content (outside of some issues with the multiple ending structure).

Instead, many Silent Hill fans who either entered the series through last year’s remake or have even been around for a while have proclaimed that Silent Hill f is “not Silent Hill” or “not Silent Hill enough”. The main reasoning for these complaints seem to be due to the change in setting to rural 1960s Japan and the centering of the psychological horror around the perspective of a coming-of-age teenage girl at the crossroads of her life at a point in history where agency wasn’t afforded to most women of her age.

These themes are weaved excellently into the game through great writing and the usual Silent Hill brand of haunting monster designs and complex puzzles that puts it directly in line with the original Team Silent entries in all the ways that count.

The reality is that the Silent Hill series has never been defined by any of the creatives who have left their mark on it throughout the years (save for maybe Akira Yamaoka and his music). Yes, it is a psychological horror series. Yes, more often than not the trauma of the protagonists are represented in the environments and monsters inhabiting them. Is it about a town in Maine? Sometimes. At least not much in Silent Hill 4. Is it about a cult in that town? Not in Silent Hill 2, although they are referenced (if you’re paying close attention to Silent Hill f, there is also a pretty substantial reference to this cult there too).

It can be argued that one of the most beloved entries in the Silent Hill series, P.T., has absolutely nothing to do with the rest of it. Save for the use of Yamaoka’s original theme at the end, the project was deliberately designed to not have you suspect that it would be a Silent Hill game until its final grand reveal. In the past arbitrary characterizations of “Silent Hill” as a brand are what led to things like the films and post-Team Silent entries forcibly incorporating the likes of Pyramid Head and the Bubble Head Nurses, which if we’ve learned anything from their handling in those works, only serves to undermine the symbolism that the monsters originally represented. In this way, Silent Hill is at its best when it’s not beholden to Silent Hill.

It’s for this reason as well that Silent Hill f is even considered by Konami to be a “standalone spin-off” of the series. It’s not to argue that any of the aforementioned elements are not important to Silent Hill, if anything it proves that the series is just as good without them. NeoBards have boiled the series down to its bare essence, a psychological horror story centered around one central character’s internal conflict, and built a foundation that future entries can now pull from as inspiration in the way that f is clearly inspired by Team Silent’s work, especially Silent Hill 3.

What Silent Hill f Represents

Given the bumpy road this far, this was increasingly necessary as entries such as Origins, Homecoming, and Downpour failed to create a bridge between the focus on their setting and characters’ psychological struggles in the way that the original entries did and now f has managed to reiterate on.

With the release of Silent Hill f, for the first time in over a decade I can confidently say that Konami is on the right track with this series. Silent Hill f is an outstanding psychological horror game that reignites the spirit of the creatives that brought us this special series through its sharp writing and horrifying themes and imagery. These are the elements that make Silent Hill games good, and it’s keeping these a priority that will ensure that we continue to get not only good new entries in this long confused series, but ones that are willing to take risks and justify the name “Silent Hill” being reincarnated in the first place.

Silent Hill f is available now for PC, PlayStation 5, and Xbox Series X/S.

What are your hopes for the future of the Silent Hill series? Let us know in the comments below.